3.2 Compliance Control Mechanisms

Compliance control mechanisms cover all the different methods and processes oversight institutions can use to supervise and check compliance with political finance regulations. Depending on the legislation in your country, your institution’s remit may encompass some or all tasks described and explained in this section: supervision and monitoring, preparation of reporting templates, receipt and review of statutory reports, handling of complaints, and audits. It may also be that other institutions are vested with some of these tasks in instances where the political finance remit is split between at least two bodies.

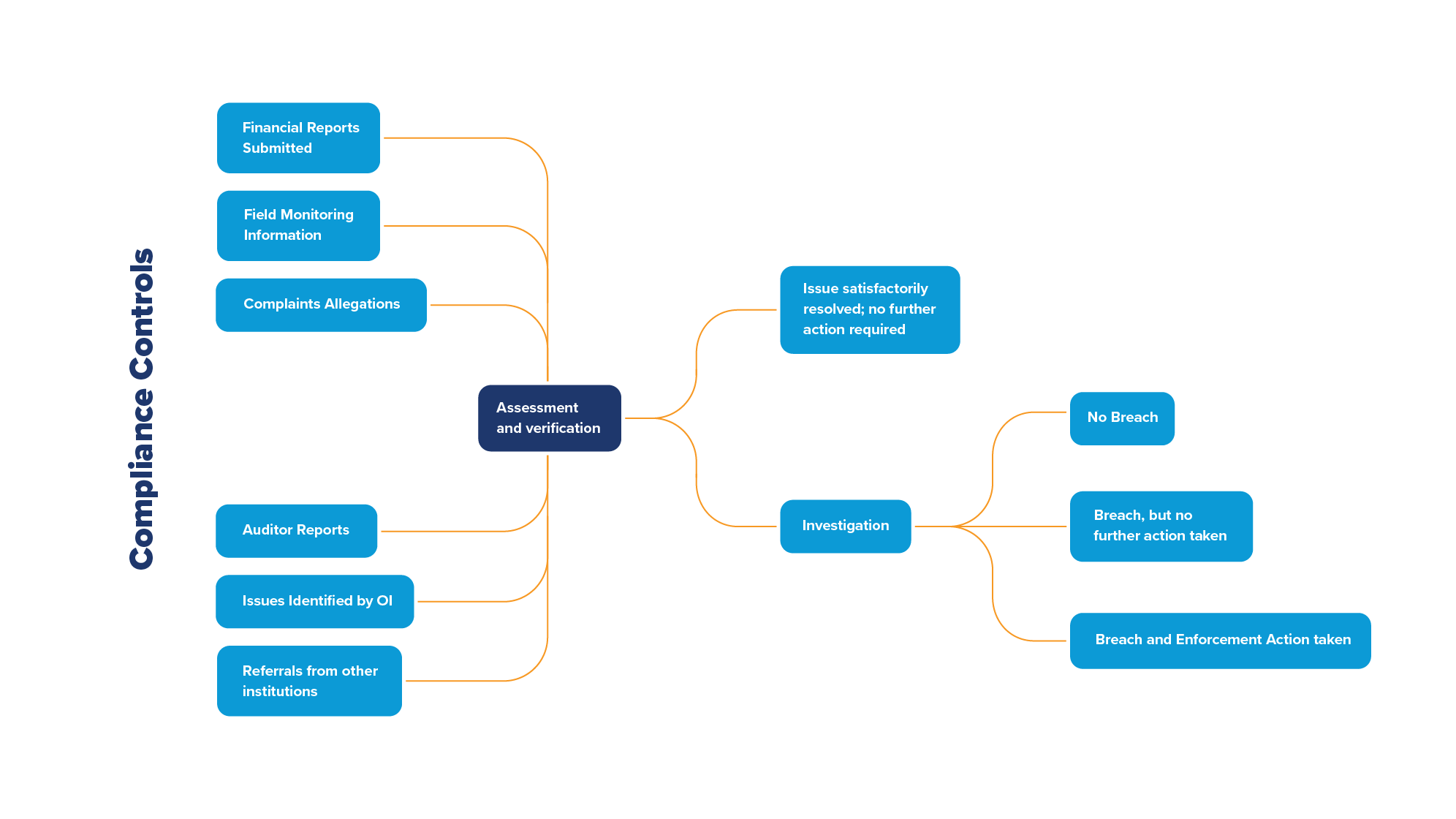

- Depending on the country’s political finance legislation and the oversight institution’s remit, regulators may have different sources of information at their disposal to carry out their oversight tasks:

- Matters raised by campaign/field monitors in monitoring reports submitted to the oversight body throughout the campaign.

- Requests, complaints, and allegations filed with the oversight body.

- Information contained in election campaign finance reports and political party annual financial reports, and issues identified by the oversight body when reviewing the returns.

- Auditors or chartered accountants’ reports.

- Matters identified by the oversight body ex officio.

- Matters referred to the oversight body by another public institution.

Compliance control mechanisms must be conducted in accordance with the oversight body’s internal procedures, which should set out the successive phases to undertake as regards the administrative and procedural review process, from the preparation of reporting templates to the receipt and recording of financial reports (and complaints), the review/audit of statutory reports, and the issuance of decisions.

Supervision and Monitoring

Supervision and monitoring are part of the tasks political finance oversight bodies can be vested with. Depending on the country and the mandate entrusted to the oversight body, supervision and monitoring of political finances can encompass different mechanisms or powers. Besides the review of financial reports, the handling of complaints and allegations and the review of auditors/accountants’ reports, the oversight institution can also have recourse to other channels of information, namely:

- Matters raised by campaign/field monitors in their monitoring reports submitted to the oversight body throughout the campaign.

- Matters identified by the oversight body ex officio.

- Matters referred to the oversight body by another public institution.

Field Monitoring

Field monitoring of election campaigns is a relatively new practice, which has recently been introduced (and sometimes incorporated in the legislative framework) in some countries, such as Albania (Field monitoring—Albania.pdf), North Macedonia, and Serbia (Serbia Case Study, Supervision and Monitoring Final Version.pdf). This usually consists of experts hired by the oversight body to observe and monitor campaign activities and election-related events during the election campaign, but it can also be conducted the oversight body’s staff. The monitoring of election campaigns can be accompanied/supplemented by the costing of observed activities. In such case, the goal is to provide to the oversight body information about campaign spending and to enable it to compare and cross-check data contained in the financial reports with campaign monitoring findings/estimates.

Real-time monitoring of election campaigns through, for instance, the establishment of a unit monitoring traditional or social media is a more common practice that can be carried out either by the oversight institution or outsourced to private companies (Lithuania) (Lithuania.pdf). CSOs can also play a significant role in monitoring campaign finances (Tunisia)

When designing your campaign monitoring program, it is important to consider the following elements if you need to issue an instruction/decision setting out the rules and the scope of campaign monitoring:

- Who will undertake the monitoring and, if it is done externally, the selection criteria, procedure, and appointment of campaign monitors, as well as the monitoring scope, monitoring period, and entities monitored.

- The geographical area of monitoring must be defined in the relevant instruction/decision.

- The monitoring scope must cover precisely the breadth of the monitoring activities; that is, monitoring of the use of campaign materials, polling stations, rallies, meetings, and events, and/or monitoring of the compliance with prohibitions and restrictions on certain activities before the election date and/or misuse of state resources during the monitoring period. Ideally, the monitoring process should be followed by a cost-benefit analysis to consider the pros and cons of such a mechanism.

- Monitoring tools must be developed by your institution; that is, reporting templates (Field monitoring template—Albania.pdf), training curricula.

- Logistical planning and development of a communication plan by your institution, especially when the monitoring involves the observation of the illegal use of state resources by public institutions.

- The mandate and powers of the campaign monitors must be clearly spelled out: Do they have to provide an estimate of the observed activities? Can they hold interviews with electoral contestants and their officers, public officials, and third parties and ask for information/documents? Can they conduct (social) media monitoring? etc.

- Whether your institution wants to publish the monitoring reports, taking into account their nature (that is, some data and facts might not be of such great interest to the public) and the impact the disclosure may have on the monitoring process (that is, some monitors could restrain themselves due to the potential public scrutiny or feel pressured to mitigate what they observed in order to avoid any kind of criticism).

Upon receipt of the campaign monitor’s report, your institution will determine whether there may have been a violation of election campaign finance rules in accordance with your internal procedures, based on the information the report contains and any comments received from the political party/candidate. Depending on the gravity of the alleged violation/irregularity, the matter might be substantively assessed for further action, immediately or during the review phase of financial reports.

Matters Identified by the Oversight Body Ex Officio

Staff members of your institution may become aware of potential violations through a number of public sources, including newspapers, television, and social media. Any staff member receiving information that appears relevant to possible noncompliance with the political finance rules should communicate that information as soon as possible to those handling such matters. The information should be registered and dealt with following the procedure in place for the receipt of complaints and allegations. Naturally, the risk may be high that there is a significant amount of misinformation or speculation among relevant information about political finance violations, and careful investigations are essential.

Your legislation may ban anonymous allegations. In those circumstances, you may need to consider whether and under what circumstances the issues raised anonymously could be addressed ex officio. For example, if accusations in an anonymous complaint are supported by publicly available information, is your institution at liberty to begin a review on its own initiative without reliance on the anonymous complaint?

For examples, see pages 7 and 8 in this U.S. Federal Election Commission document and here about Montenegro (Montenegro.pdf).

Matters Referred to the Oversight Body by Another Public Institution

It may happen that elements regarding a potential breach of campaign finance or political party financing regulations is referred to a political finance oversight institution by another public institution. For instance, the media regulator might receive a complaint or allegations of wrongdoings regarding political advertisements placed on social media by non-contestant campaigners. Although the media-related part of that complaint may fall under the jurisdiction of the media regulator, accusations pertaining to non-contestants and political advertising might need to be handled by your institution, and the media regulator may therefore refer that information to you. In some cases, referring relevant information between institutions may be mandated by law.

For example, in the United States, enforcement proceedings may also originate from other entities referring potential violations to the Federal Election Commission (FEC). These entities include local and state law enforcement authorities, federal enforcement authorities, and other federal agencies—see pages 8 and 9 in this FEC document.

Preparing Reporting

A cornerstone in political finance transparency is the financial reporting system for political parties and election contestants, whether it relates to annual or ongoing party finance reports or to campaign finance reports submitted before or after an election. Oversight—Toolkit for Political Finance Institutions covers various areas of your work with financial reporting, from strategic planning to receipt, review, and publication of financial reports.

If you do not carefully consider how political parties and election contestants (and potentially others) should prepare and submit financial reports, there is a significant risk that your other activities will not be successful in achieving transparency and control over money in the political process. Even a perfect reporting system will not provide transparency if parties and electoral contestants can with impunity refuse to declare their income and spending, but if the reporting system is not well designed, even actors who wish to comply and be open about their finances may be unable to do so.

There is much that can be learned from the experiences in other countries regarding financial reporting, as outlined in this section. Ultimately however, the most suitable approach for you will depend on your country context. Therefore, it is important that in-depth discussions are held with stakeholders ahead of the development of a reporting system.

It can be argued that anyone wishing to form a political party or run as an election candidate must accept and comply with legislation and regulations on financial reporting. However, experience shows that when the reporting systems are not suited to the local context, the level of compliance suffers and confidence in the entire system of political finance oversight may also suffer.

The OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights and the Venice Commission recommend that “The law should define the format and contents of the reports to ensure that parties and candidates disclose essential information” (see Article 259). However, some flexibility in reporting structures may be useful, as it allows you to engage stakeholders in an ongoing dialogue about the most effective form of reporting, and to make minor changes, as required.

Of key importance is the holding of a dialogue with political parties and others whom legislation requires to submit reports. If the reporting system does not take into account the way that political parties gather and maintain financial information, the risk of noncompliance increases. You should also consider the capacity of candidates at all levels of elections to prepare and submit financial reports. However, you retain the final decision on the system to be used (not least since political actors may try to get out of reporting sensitive information). After each reporting deadline, gather representatives of the reporting entities and discuss reforms of the reporting system that may be desirable.

You should also bear in mind input from other stakeholders, including civil society groups and journalists who may use financial reports in their work and who may (formally or informally) assist your institution in controlling the accuracy of reports. Note, however, that such groups sometimes overestimate the capacity of political actors to comply with reporting requirements. Outside groups may also wish to go straight to an advanced reporting system, bypassing the gradual adjustment to detailed reporting that may be needed in most countries.

As necessary, you may also wish to consult state audit or accounting institutions to ensure that the reporting format is in line with legislation on financial accounting or auditing. This may be especially important in cases where reports have to be formally audited before or after they are submitted.

In addition, in developing the financial reporting system you should consider the way that the financial reports are to be published by your institution. The preparations for reporting and for the publication of reports go hand in hand, and they should always be considered together.

See here for an overview of reporting requirements and processes across Europe (IIIDEM case study reporting disclosure - unit5.pdf).

These are some of the things you need to carefully consider when preparing for financial reporting:

- What information should you require to be included in reports?

- Should you require the inclusion of supporting documentation?

- What should be the format of the reporting?

- What guidance do you need to provide to ensure compliance with the reporting system?

What Information Should You Require to Be Included in Reports?

This text is taken (with minor modifications) from the IFES TIDE Political Finance Oversight Handbook.

Request All Information Required by Law

Where there are legal requirements regarding the information political actors need to submit, the regulator must ensure all such information is covered in the reporting forms. However, it is more common that legislation gives only overall guidance about the data that must be submitted. In such cases, you will need to develop more detailed political finance disclosure regulations, if it is within your legal mandate to do so. Such regulations may include the reporting forms themselves; if they do not, the forms should be developed in close consultation with those required to submit financial reports.

Request Additional Information Necessary to Ensure Compliance With Legal Provisions

As mentioned, legislation often lacks detailed guidance regarding the information political actors must submit. Often, legislation does not even specify if financial reports need to reveal the identity of donors. In such cases, you must identify the information necessary to monitor the accuracy of financial statements and compliance with political finance regulations.

For example, even if legislation does not require that political actors report the names of contributors, you must have access to this information if you are required to enforce a ban on anonymous donations or a limit the amount contributed over a certain period of time.

Do Not Request Information You Do Not Need

You should not require just any information through the reporting forms. A rule of thumb is that you must have a clear idea of how you would use each piece of information that is requested. That certain information could be useful is not a sufficient argument for requiring political actors to report it, given the administrative burden that reporting entails.

Ensure the Reporting Format Does Not Overburden Political Actors Who Must Report

An important principle is that the reporting system must be such that political actors can be reasonably expected to comply with the requirements without hindering their ability to run effective campaigns. For example, reporting thresholds can be used to reduce the need for time-consuming reporting of unimportant transactions. This might lead you to decide that only expenses above a certain amount or assets exceeding a certain current market value should be reported. There is little point in demanding political parties to report on, say, every single pencil in their possession. Demanding that receipts are provided for every donation, signed by both the financial agent and the donor, can be a good way of tracking larger donations, but it is unreasonable to demand such records for donations of very little value.

Some countries use a threshold for donations that have to be reported in detail. In the United States, it is $200 (USD) in a year, while in Australia it was $14,500 (AUD) as of the middle of 2021. Of course, a threshold of this kind opens the risk that wealthy interests will divide their donations to escape publicity. If the threshold is set low enough, donors will have to do a lot of work to get around reporting requirements.

The principle of not overburdening political actors also relates to the frequency of reporting and to the time between the deadline for submission and the closing of books for a report (for example, at the end of a calendar year or shortly after an election).

Do Not Use More Reporting Forms Than Necessary

In line with the principle of not overburdening political actors, the reporting format should be as streamlined as possible. Actors should not be required to repeat the same information several times in different forms (in some cases, it can be possible to find solutions where information entered in one form is automatically used to populate parts of other forms). You should try to provide a logical sequence of forms so it is clear how the different forms and items therein relate to each other. For example, if a summary form asks for total value of donations in the form of real estate, the form listing individual contributions should require the actor to note the same information so it can be transferred to the summary form.

However, this principle does not necessarily mean that reducing the number of forms is always advisable. The reporting format should, above all, be easy to understand. Combining many items on the same form can cause confusion. Consider if different actors should use the same forms for their reporting, or if candidates and political parties (if both need to submit reports) should use separate forms. The former solution will reduce the number of forms in use, but it could also lead to various sections of forms only applying to some actors (such as “constituency contested”). Consider also if it is possible to use the same forms for campaign finance and for annual reporting.

Avoid Terms and Concepts That Are Not Clearly Defined

While it is tempting to ensure standardization through applying various terms and concepts, caution must be exercised to avoid confusion. Requiring political actors to break down their expenses into campaign and administrative costs, for example, (and subcategories within each), may be a good idea, but it will still be difficult to compare the information received unless clear rules are set for how expenses should be categorized. This principle goes beyond defined concepts in accounting. For example, in some countries, the regulator asks the profession of contributors. Assuming this inclusion is not a legal requirement, the purpose of the regulator in asking about the profession of the contributor is often that this information will make it easier for them to judge if individual contributors can be expected to own the amounts they are reported to have contributed. However, unless there are legally defined professions, such a requirement is unlikely to enhance transparency. Anyone can, for example, call themself a “businessperson” or “entrepreneur.”

For Campaign Finance Reports, Consider Variations Depending on the Type of Elections

While the principle of campaign finance transparency is the same for all types of electoral processes, it may not be feasible to require the same level of reporting of presidential, parliamentary, and local government candidates alike. In most countries, presidential candidates are likely to have a team of people overseeing their campaign finances, and it is reasonable to expect that a presidential campaign can provide detailed information about how it raised and spent money. Take into account, however, that since in most presidential elections the entire country is part of the electoral area, it can take time for presidential campaign teams to gather, prepare, and submit financial information about their activities.

Parliamentary candidates may have less administrative capacity for bookkeeping and financial reporting than presidential candidates. However, in single-member-district electoral systems, parliamentary candidates have a significantly smaller electoral area to deal with, and regardless of the electoral system, they are likely to have a significantly less complicated financial structure than presidential candidates. This should be taken into account when deciding on the reporting system for each type of election.

Assuming that candidates in subnational elections are required to submit financial reports, particular care is needed in considering what information that they can be expected to collect and submit. The number of local government structures, and hence of candidates to such structures, may be significant (for example, by late 2021 there were 283,350 “local bodies” in India).

Your institution should engage local government bodies, political parties, and past candidates in a discussion about what information local government candidates can be required to submit, in what format, and at what time.

The points noted above should also be considered, as appropriate, when it comes to campaign finance reporting by nominating political parties or other structures (such as citizen initiatives) in relation to different types of elections.

Should You Require the Inclusion of Supporting Documentation?

Legislation may specify in detail what, if any, supporting documentation political parties and election contestants are required to submit with their financial statements. When this is the case, your task as an oversight institution is to ensure that the reporting entities are aware of this and, as suitable and necessary, to assist them in how the relevant supporting documentation can be acquired and submitted to you.

In many countries, however, legislation does not specify in detail or at all what, if any, supporting documentation needs to be submitted. In such situation, it is important to carefully consider what should be requested.

Requiring the submission of detailed supporting information can assist your oversight institution in reviewing the accuracy of submitted financial statements. Indeed, such controls and audits may be very difficult or impossible without access to supporting documentation. Given this, you should carefully consider the implications for controls of audits of submitted financial reports if you require the inclusion of certain supporting documentation.

On the other hand, requiring masses of supporting documentation may prove unduly burdensome for the political parties and electoral contestants, and also for you as the oversight institution. The same principle as discussed above about only asking for information in reporting that you are likely to use also applies to supporting documentation. You may also wish to vary the amount of supporting documentation that electoral contestants are required to submit depending on the type of election, requiring less supporting documentation for local government elections than for presidential and parliamentary elections.

You may require that those who must submit financial reports maintain records of supporting documentation that they are not required to submit. In such cases, you may request the submission of such documentation at a later stage, in particular if a need arises for an investigation of the submitted financial records or other activities. Do not automatically assume that requiring the submission of supporting documentation is never necessary as long as it can be requested later, since requesting the later submission of such documentation can be a demanding and time-consuming process.

What Should Be the Reporting Format?

There are many different ways in which political parties and electoral contestants can submit information about their financial activities to your institution. The main options are:

- Hard copy (paper) format only.

- Hard copy (paper) format together with electronic submission (any of the options below):

- PDF documents.

- Machine-readable documents such as Microsoft Excel ones.

- A dedicated software solution installed on the user’s computer.

- An online system

Hard copy (paper) submission may be most suitable where those required to submit information are unlikely to have access to a computer or may not have the necessary experience needed to use an electronic submission system. This may apply, for example, to local government candidates in countries with limited computer penetration. Unreasonable demands for the use of IT must not threaten or limit the freedom to run for office, as described in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

A legal requirement that financial reports must be physically signed does not immediately preclude a system of electronic reporting. A framework can be set up whereby the political party or candidate submits the financial report in a signed hard copy (paper) format and also electronically, increasing the opportunities for control of the reports and for publication. While double-reporting should be avoided in general, this may be a suitable solution in case of legally required hard copy signatures in contexts where submitted hard copy reports are simply printouts from the party’s or electoral contestant’s computer system. If a legally accepted system for electronic signatures is in existence, you should explore how it can be used to satisfy requirements of submitted reports being signed.

Whenever suitable, depending on the capacity of stakeholders, electronic submission is preferable as it allows for easier review, analysis, and publication of received information. A lot of information about electronic reporting is available in International IDEA’s Digital Solutions for Political Finance Reporting and Disclosure report.

Demanding the submission of PDF documents is normally a substandard solution, as such documents are often not machine-readable and the data can therefore not easily be transferred into a database for review and publication. Even such a basic tasks as summing up the amounts of donations made by the same person (required whenever there is a legal personal donation limit) can be very demanding if reports are only available in PDF format. There is the option of creating PDF forms that users can fill in as these are normally machine-readable.

A comparatively straightforward solution is to develop and share the reporting forms in a commonly used format such as Microsoft Excel. Such forms can be modified on the computer of the reporting entity (including by using free software) and submitted to you via email or (less desirably, due to the risk of computer viruses) USB memory sticks. If you use this approach, consider electronically locking any parts of the document that you do not wish the users to be able to edit, so they do not intentionally or unintentionally make edits that may hinder the movement of data from the document into an online database. It is strongly advised that you consult an IT expert to make sure that the electronic reporting documents are suitable for filling in and for the data to be exported into a database that you control.

Providing a specialized software for financial reporting is not a very common approach. The Federal Election Commission in the United States uses its own FECFile software, which is free to download but can only be used on the computer in which it has been downloaded. A similar system is used by Elections Canada and by Brazil’s Tribunal Superior Eleitoral.

In most cases where political finance reporting systems are being reformed today, the preferred choice is to build a system in which users upload information to an online system maintained and/or designed by the oversight institution. Such systems do not require software to be up to date and can be easily modified. There are many different options for online reporting, and it is again strongly advised that you consult an IT expert in the development of a system of this kind. For a list of online reporting systems, see Annex A in this document.

Many online reporting systems combine the direct entry of certain information with the uploading of electronic documents. Such an approach has many advantages, as it can be very time-consuming for users to enter large amounts of information directly into the system. The same considerations as discussed above regarding the likes of PDF and Microsoft Excel files also apply when political parties or electoral contestants upload files in an online system.

Online systems can also allow for political parties and electoral contestants to submit data according to the requirements that are related to each entity—for example, in Spain, certain parties are by law allowed to use a simplified reporting process, and both this and the full reporting system are accounted for in the online submission system.

Where reports are submitted electronically, consider how you can ensure that only eligible persons submit such information to you. Some countries have a national system for electronic reports (for example, Iceland) or a national system for electronic bank-IDs (for example, Sweden). In other countries, the political finance oversight institutions provide log-in details to relevant persons from political parties and election campaigns. This is, for example, the approach taken by Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Central Election Commission and the United Kingdom’s Electoral Commission.

As with any electronic systems, the development of an online submission system must include safety consideration, such as the risk that unauthorized persons may attempt to disrupt the process by uploading inaccurate information or deny access to the system for regular users. While most of the political party and campaign finance information that is submitted will be made available to the public, there can be cases where certain information that is submitted will not be published. This can include the full address of donors or the identity of donors giving below a set threshold. In such cases, it is especially important to ensure that this information is protected from unauthorized persons. In this too, you are strongly advised to seek guidance from IT experts on the security aspects of the electronic system.

Ukraine’s National Agency on Corruption Prevention has provided a case study of the country’s recently developed system for online reporting (UKR_NACP Launch of POLITDATA.pdf).

What Guidance Do You Need to Provide to Ensure Compliance With the Reporting System?

In parallel with developing the system for reporting, make sure that you also develop clear guidance materials for those who will be required to submit financial reports. This can include written manuals, videos, and infographics, combined with trainings and FAQs on your website. For more on the issue of guidance, see here. Ukraine’s National Agency on Corruption Prevention has published a good example of FAQs on how to use an online reporting system. In South Africa, the Political Party Funding Act Regulations 2021 includes information on how to submit financial reports, opting for though the use of a paper-based system may have been the missing of an opportunity to make the provisions of the 2018 Political Party Funding Act (which came into force in 2021) truly effective.

Receipt and Review of Statutory Reports

The financial reports submitted by electoral contestants as regards the financing of their election campaigns and by political parties about the financing of their routine activities are the primary sources of information to carry out your supervision tasks.

The existence of internal procedures that set out rules pertaining to receipt and review of financial reports will help guide staff members on how to handle statutory reports within a clear, impartial, and coherent framework, and will also help your institution demonstrate fairness, impartiality, and quality control at all times.

It is good practice to record all financial reports submitted to the oversight institution, whether within or after the legal deadline. Ideally, all reports received should be recorded in an IT-based system to flag any late filing and to facilitate the review process.

Depending on your country’s legislation and your institution’s remit, the review of the financial reports could encompass distinct phases of control or be undertaken all at once. Either way, it is good practice to notify to the electoral contestants and political parties all irregularities, discrepancies, or breaches that could lead to the launching of an investigation and/or the referral of the case to law enforcement agencies or prosecutorial authorities.

Receipt of Statutory Reports

Depending on the applicable legal framework, financial reports can be submitted in hard copy, through entries on the oversight body’s website, and/or in electronic formats. In order to enhance compliance with reporting requirements, a significant number of oversight institutions put out reminders on their website or in their manuals/handbooks regarding the filing deadlines for the financial reports (see the Election Canada website and this document explaining the process of France’s Commission nationale des comptes de campagne et des financements politiques (CNCCFP website.pdf). This can also be accompanied by the sending of letters or emails to electoral contestants at the beginning or just before the end of the election campaign to remind them of their obligations and the reporting timeframe. While it is the responsibility of the reporting entity to submit reports correctly and on time, noncompliance reflects badly on the oversight institution also, and it should therefore spend much effort on ensuring a high compliance rate.

Ideally all received reports should be recorded in your register or intranet/information system with the mention of the submission date of the hard copy (if applicable, mention of the submission date of the electronic date as well), and it should be assigned a file number. The use of e-reporting systems, if you have such a system in place, will help flag irregularities as regards the receipt of financial reports.

Statutory reports can be submitted within the legal deadline or can also be lodged after the legal deadline or not submitted at all. Late submission of reports or failure to do so at might trigger the sending of a request by your institution to ask the political party/candidate to regularize the situation or to warn them of a sanction for the identified irregularity.

Review of Statutory Reports

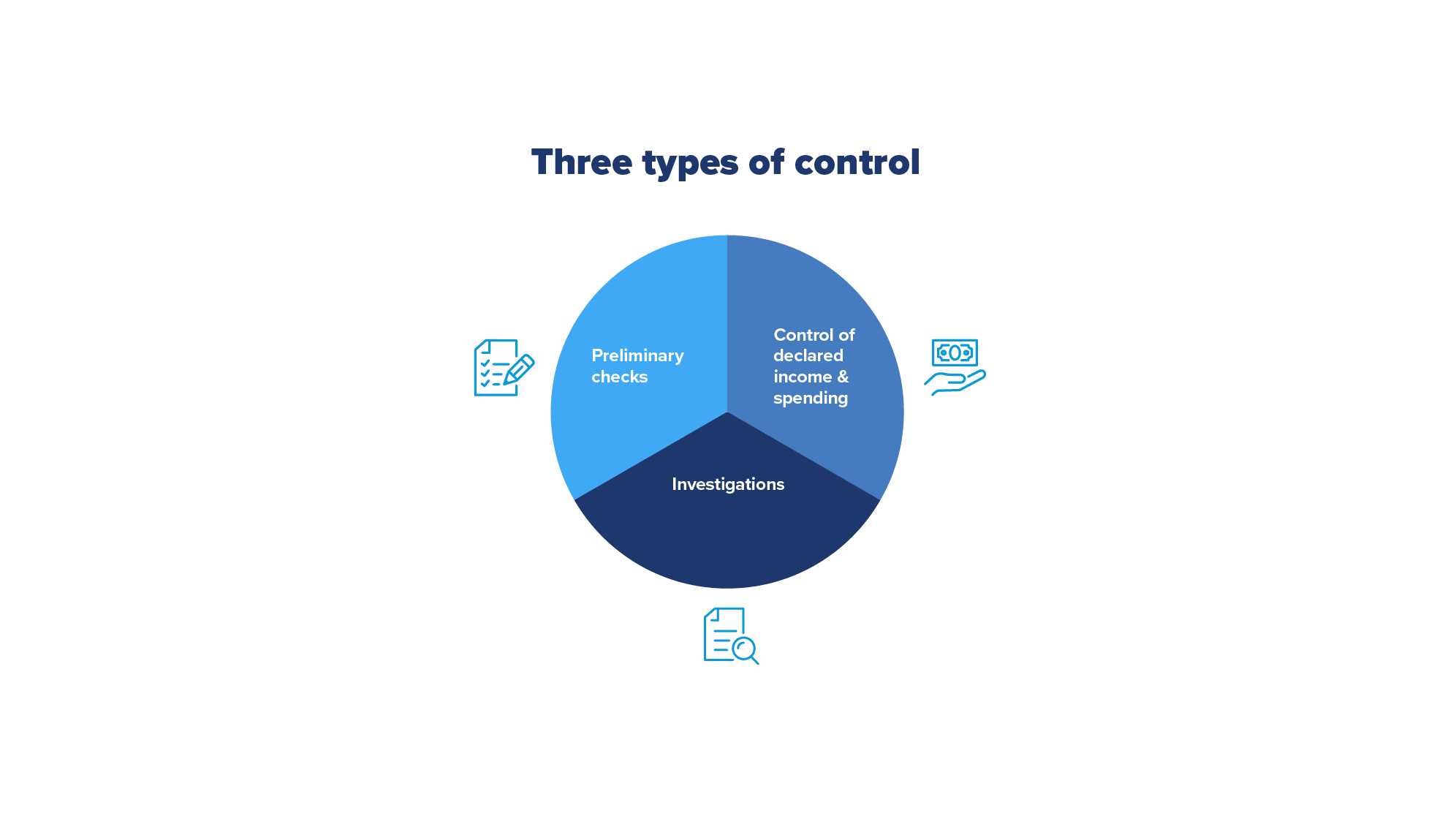

The review of financial reports consists of at least two phases and sometimes three:â¯Three types of control.pdf.

- Preliminary control of submitted reports to detect any readily apparent problems.

- In-depth controls taking into account the different sources of information the oversight body has at its disposal.

- Investigationâ¯of irregularities/violations detected during one of the first two phases

Prioritization Risk register

Some oversight institutions use a risk register to rationalize and prioritize their workload. This internal document helps identify risk areas and red flags (Table of risk areas AND red flags.pdf), for developments whose likelihood to occur and potential impact on the campaign/political party routine activity are the most likely to have a significant influence on the electoral or political process. The risk criteria elaborated by the oversight institutions aim to determine:

- Who is subject to its control, taking into account written, objective, and clear factors, such as the financial resources of the electoral contestants (main political parties/candidates with significant support and electoral results) or the apparition of new political actors (newcomers with some strong and wealthy supporters)

- The kind of activity to control as regards income, such as donation or loan patterns, or the use of payment platforms toâ¯bundle donations for a specific electoral contestant.

- The kind of spending to control, such as electoral rallies/meetings (potential cases of abuse of state resources, vote buying), billboards, digital spending, and the use of portals for paid political advertising, taking into account their importance, sensitivity, and impact on the electorate.

- When the control happens: before, during, and after the election campaign or on a rotating basis for political party routine activity.

See the risk profile system used by theâ¯U.K. Electoral Commission, which remains relevant although it has been discontinued.

Preliminary Analysis: Detection of Readily Apparent Problems

The goal of preliminary control is to ensure that the financial reports meet formal requirements and to detect readily apparent problems, using no other data than the reports themselves.

Formal Requirements

| Issue | How to control |

|---|---|

| Financial agent appointed |

Check appointment documents/date of the financial agent |

| Dedicated bank account opened |

Check documentation provided to ensure the opening of the bank account |

| Report submitted (on time) |

Keep records of received mail/usage of online reporting and stamp with date of receipt (manually/electronically) |

| Report signed |

Check signature of correct person included |

| Report complete and accompanied by supporting documentation |

Check all cells/pages are completed and supporting documents are provided |

When carrying out the preliminary verification, you may want to check whether:

An official agent responsible for financial matters has been appointed, if the law foresees such an obligation.

The report has been submitted within the legal deadline, in the prescribed formats in the legislation, and signed by the competent person(s).

The report appears to complete (all relevant pages/cells are completed) and is accompanied by all supporting documentation.

The existence of checklists/dropdown menus in your information system might help your staff members carry out this part of the control process. Some options presented below might be irrelevant depending on the existing political finance regulations into force in your country.

| Format of Reports | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Was the report submitted on time? | ||

| Has the reporting template been used? | ||

| Has the report been submitted in hard copy and/or electronically and/or through entries on your website? | ||

| Have all pages been completed/filled out? | ||

| Is the report signed by the competent person(s)? | ||

| Content of Reports Submitted | ||

| When was the financial agent appointed? If applicable | ||

| Does the bank account number provided match the account designated by the political party/candidate, if applicable? | ||

| Is the election finance campaign report balanced or in surplus? | ||

| Does the total amount of in-kind contributions correspond to the total amount of in-kind expenditure? | ||

| Are the declared expenses within the spending limit? | ||

| Supporting Documentation | ||

| Are bank statements provided? | ||

| Are donor declarations provided, if applicable? | ||

| Are contracts for goods and services provided? | ||

| Are invoices for goods and services provided? | ||

| Is the documentation pertaining to the valuation and calculation of in-kind donation/spending reported provided? | ||

| Are specimens of electoral materials provided? |

It is good practice to prepare a list of all entities required to submit reports in order to keep records of the ones that have filed within or after the legal deadline or any agreed extended deadline, and the ones that have not filed, especially if your institution is not equipped with an online reporting system.

Depending on the regulations in place in your country, the preliminary control may be undertaken of all reports filed, whether within the legal deadline or late. Regardless of the submission format used, it is important to keep records of all received letters and e-mails, together with the manual stamp/electronic submission date of receipt of the reports.

During this first phase of control, your staff members may detect irregularities or inaccuracies that will need to be regularized. Your internal procedures may foresee the possibility to ask for further information or to accept or reject the report. In case it is concluded that the report should be rejected, potentially after requesting further information/regularization, it is good practice to send to the concerned electoral contestant a letter specifying the defects found, the steps the political party/candidate should take and a deadline for doing so, and the potential legal consequences for failing to take the specified action.

In-Depth Control of Final Election Finance Reports

The in-depth or substantive control of declared income and spending aims to check the compliance by political parties and candidates with provisions of the legal framework. To do so, oversight bodies usually check the submitted reports and compare the reported financial information with other data sources to control accuracy.

To this end, your institution may carry out some or all of the tasks below:

- Controlling the documentation of income and ensuring the permissibility of donors and that donations or loans made are within the legal limit(s).

- Controlling the documentation of spending, checking for elections that expenses have been incurred for electoral purposes, and ensuring that reported expenses are within the spending limit(s).

- Checking whether the total amounts of income and spending declared by political parties/candidates match the amounts mentioned in the supporting documentation and the accounting books.

- Comparing the amounts declared by political parties/candidates with any information contained in the interim reports (if applicable), gathered throughout the campaign by field monitors (if applicable), or gathered by/available to your institution or contained in complaints/denunciations received.

- Controlling that the financial reports, based on the information submitted, do not reveal any violations of the law pertaining to the sources of income or expenditures.

You can find a detailed description of the approach of the oversight institution in France to checking campaign finance reports (Country example / France - In-depth control of final election finance reports.pdf), including its checklist for controlling political party annual financial reports (Checklist for controlling political party annual financial reports.pdf).

In Montenegro, the Agency for Prevention of Corruption has provided a description of how it reviews received financial reports (Country example / MontenegroâAgency for the Prevention of Corruptionâs review process of the financial reports submitted by political entities and on cooperation mechanisms with the State Audit Institution (SAI).pdf).

Control of Declared Income

The main goal of the control of declared income is to verify whether funding comes from permissible contributors and whether the amounts declared match the amounts mentioned in the supporting documents and bank statements. This control is based on the information and documents submitted by the political party/candidate in their reports, but also resorts to the use of bank statements and all other relevant documents (loan documentation, institutional registries, etc.) to check the permissibility and legality of the sources of financing declared.

The first step consists generally of checking the amounts declared by type of revenueâ that is, donations, loans, self-financing, political party contributions/income-generating activities/membership feesâand ensure that the total of declared income matches the individual amount for each type of reported source of financing. Once the first series of checks is done, the second step usually consists of reviewing the correspondence between the information contained in the report and the information contained in the supporting documents. To do so, it is good practice to check each source of income reported against the bank statements and ensure that:

- Each monetary income collected and reported is traceable and corresponds to a single financial transaction on the bank statement(s).

- The date of each transaction is clearly mentioned and verifiable.

- The amounts declared match.

- The origin of the income declared (name of the donor/lender/party contribution/party member/source of the party income) aligns with the information mentioned on the bank statement(s) and/or on the institutional registers/registries to detect impermissible donors (foreign/anonymous donors, donations made in the name of another).

It is also good practice to check each in-kind contribution reported against the supporting documents. Each in-kind contribution should have its equivalence in spending in order to detect whether there are unreported/underestimated/undeclared in-kind contributions or in-kind contribution disguised as volunteer activity.

Having checklists/dropdown menus in your information system is a very helpful tool to enable the control over the permissibility requirements and the compliance with donation/loans limits. There are a variety of methods used for checking the permissibility of donations depending on country context and other factorsâthe approach used in several countries is outlined in this document (Case study on permissibility of donations.pdf). Depending on the regulatory situation in your country, controls of income may also include the use of certain forms of bank transactions, the use of cryptocurrencies, and related issues.â¯

Some options presented below might be irrelevant depending on the political finance regulations in force in your country.

| Requirements | How to Control? What to Control |

|---|---|

| Donations | |

| Donation originates with permissible donor (individuals) (nationality, age, situation) | Cross-check with social registry Cross-check with civil service registry Cross-check with electoral roll to detect donations from foreigners or minors. |

| Donation amount seems to be in keeping with donorâs financial resources | Cross-check with tax registry and tax/income records to detect suspiciously large donations |

| Donation originates with permissible donor (domestic legal entity, no government contracts) |

Cross-check with registry of legal entities and/or company registry |

| Donations within legal limits | Aggregate donations from a same donorâcalculate total value of all donations from one donor to the same recipient |

| Loans | |

| Loan originates with permissible donor | Check the identification number on the appropriate state register |

| Loan amount seems to be in keeping with lenderâs financial resources | Compare loans with tax/income records to flag suspiciously large loans (that could possibly be written off) |

| Terms of loan consistent with fiscal legislation? | |

| Loans within legal limits | If applicable |

| Personal funds (elections) | |

| Self-funding seems to be in keeping with candidateâs financial resources | Compare personal funding amount with tax/income records to assess if there are red flags about the funding being really personal |

| Party funds | |

| Funds transferred should be from commercial activities such as publications, printing presses, services, leasing, or membership fees | For membership fees, trace source of funding back to party members Cross-check with last annual financial statement |

| Political party donation | Review and cross-check with last annual financial statement |

Control of Declared Spending

The main goal of the control of declared spending is to check whether reported expenses were incurred for electoral purposes or for political party routine activity purposes, and to detect any potential overspending, underestimated spending, unreported spending, or illegal expenses (abuse of state resources /vote buying) of submitted financial reports. This control is based on the information and documents submitted by political parties/candidates in their reports, but also on bank statements and all other relevant documents (invoices, contracts, specimens of electoral materials, etc.) to check the legality and accuracy of the spending reported. For a case study exploring the review of overspending by President Nicolas Sarkozy in the 2012 presidential election in France, see here:â¯Case study on overspending.pdf.

The first step aims to check that all categories of spending are duly reported and that amounts of the different categories of expenses, whether paid or in-kind expenditure, add up.

Once this step completed, the second phase of this control generally consists of assessing the validity and accuracy of the spending declared by:

- Comparing each declared expenditure amount with the amount shown paid in the bank statement.

- Checking the accuracy of the amount declared against the documents provided (invoices, quotes).

- Confirming that expenses declared have actually been paid (for example, no outstanding/unpaid debts) by cross-referencing with bank statements.

- Controlling the invoices to ensure the validity of the declared expenditure (for example, sales tax/value-added tax, information related to vendors/suppliers; checking that the quantity of items ordered or the scope of services provided reflect reality and that the price per item/service appears reasonable).

- Establishing that the spending declared has been incurred for electoral purposes (for elections).

- Checking that the declared expenses are within the spending limit (for elections) and that the spending on a certain category (such as media advertising) does not exceed a certain value (as is the case in, for example, Lithuania and Poland).

- The analysis of declared spending can then lead you to draw conclusions and to compare reported amounts between different election campaign finance reports, and it can help your staff members flag elements that might appear suspicious.

Case Processing

At the end of the control process, you are most likely to find out the following types of irregularities:

- Absence of supporting documentation.

- Discrepancies/inconsistencies between amounts declared and supporting documents provided.

- Donations above the limit or not made in the dedicated bank account.

- Problem with the valuation of in-kind contributions/expenses.

- Problem of accounting of expenses declared (underestimation/overestimation).

- Impermissible donations.

- Problem of tax invoices/global invoices.

- Absence of electoral nature of expenses declared (for elections).

- Omission/partial accounting of electoral expenses (for elections).

It is good practice at the end of the in-depth control that staff members draft a report highlighting the issues identified during the control and documenting the results of the review process. It is common that the review process be accompanied by the carrying out of administrative/adversarial proceedings to seek explanation from political parties/candidates and to identify information and documents that are needed to complete the substantive control. Regardless of your internal procedures, it is critical that your letter to the political party/candidateâs sets a deadline for them to reply and informs them of what subsequent actionâ¯may be takenâ¯in case of failure to address the issue(s) or to answer the request.

As part of the in-depth control, your staff members will need to consider the findings and conclusions set out in the financial monitor and auditor reports (if applicable) to assess:

Whether the election finance report substantiates or negates the findings raised in the monitor/auditor report.

Whether the monitor/auditor report raises novel legal issues that need to be referred before proceeding further.

Depending on your remit, you may also take into account information contained inâ¯complaintsâ¯and obtained from any person/entity who may reasonably have relevant information (broadest remit) or from political parties/donors (limited remit).

Complaints and Allegations

What Are Complaints and Allegations?

In this section, complaints and allegations refer to accusations that someone has broken the rules governing political finance. The term “complaints” could also be used in situations where it is suggested that the oversight institution itself has not acted appropriately, but those situations should be dealt with by the institution’s own procedures.

Even when you, as an oversight institution, provide advisory services, there will be times when the rules might be broken.

There are different ways to handle complaints and allegations, depending on a country’s legal framework and traditions. In a significant number of countries, rules regarding the handling and examination of complaints and allegations are spelled out in a code of/law on administrative procedure. In these countries, the guiding principles, the examination and review process, and the appeals mechanism are stipulated in a legal act. In other countries, the procedures regarding the handling and examination of complaints and allegations are encompassed in the political finance legislation or fall under the regulatory powers of the oversight institution. Given the diversity of legal and procedural systems pertaining to the submission of and dealing with complaints and allegations, some mechanisms or concepts described below will not be relevant to your system.

It is not just legal and procedural systems that vary from country to country; so can the terms used. In some legal systems, “complaints” are formal documents that must be lodged with a court or tribunal and “allegations” (sometimes called denunciations) are requests that can be filed with an institution/administrative body. In countries where complaints must be filed with a tribunal or court, often the oversight body will only be responsible for dealing with allegations. In other countries, no distinction is made between complaints and allegations and often the oversight institution’s remit is broadly drafted to encompass all suggestions of wrongdoing. Even for countries in this latter category, there may be significant variations. For example, in some countries the oversight institution must pass criminal matters to the police or prosecutorial authority for investigation. In other countries, the oversight institution might defer cases involving criminal breaches until the conclusion of the criminal proceedings. You will need to select the information most relevant to your own jurisdiction from the material in this section. The terms “complaint” and “allegation” are used interchangeably in this section, and you determine what practice pertains to your legal system.

Who Can Make Complaints/Allegations?

Complaints/allegations can be an important means for oversight bodies to learn about possible breaches of law/regulations. Therefore, it is good practice that the least restrictions possible be placed on who can make an them. Encouraging allegations as much as possible does carry some risks, but there are other ways to manage this than by restricting who can make one.

Questions may arise as to whether you should accept anonymous complaints/allegations. The first consideration is whether the applicable legal framework addresses the permissibility of anonymous allegations. If the legislation bans them, you may need to consider whether and under what circumstances the issues raised anonymously could be addressed ex officio. For example, if accusations in an anonymous complaint are supported by publicly available information, is your institution at liberty to begin a review on its own initiative without reliance on the anonymous complaint? One could argue that where a power is inherent in your authority to act ex officio, to ignore such information would require your institution to turn a blind eye to violations of the law.

Where there is no legal prohibition on anonymous allegations, you may need to consider whether to accept complaints from unidentifiable sources. There are advantages and disadvantages to accepting them. Some complainants may wish not to be identified for good reasons, such as fear of reprisal. On the other hand, allowing anonymous allegations can also encourage groundless allegations submitted for political reasons. In the United States, complaints must be signed and sworn to under penalty of perjury. In the United Kingdom, some complaints must be dealt with by the police and increasingly police forces are asking complainants to make a formal statement rather than accepting a letter. In both cases, the rationale behind such stringent requirements is to make complainants think carefully about whether they wish to be accountable for the complaint they file.

With an effective preliminary assessment or triage process in place, however, groundless allegations can be identified and dismissed; a blanket refusal to accept anonymous allegations risks excluding important information about noncompliance with political finance laws. If you do accept anonymous allegations, you will need to consider how they can be made—most electronic or online methods will not be truly anonymous because the denouncer could be traced, and some people may therefore not trust those methods.

How Will You Allow Complaints/Allegations to Be Made?

Complaints/allegations can be made in many ways, and it is important to be clear which ways are allowed in your jurisdiction. It is common to require complaints/allegations to be in writing, so that there is no dispute over the content, which could happen if it is accepted via a note of a phone call. But it is important to consider whether anyone might not be able to make a written complaint/allegation (for example, because of a disability or language difficulties), and to have an alternative method to achieve a written record, agreed with the complainant, available if needed. Such an obligation is legally imposed in many jurisdictions. It may mean allowing a complainant to come to your office to relay orally their complaint, which you then transcribe into the required written format.

It is common to accept complaints/allegations by email, and some countries have recently developed other electronic methods such as dedicated portals/platforms specially designed to receive them. See, for example, the complaints system used by Albania’s Central Election Commission while Lithuania’s Central Election Commission uses an “advertising trap” portal.

It is good practice to make ways of making complaints or allegations as accessible as possible. Allowing only one method might exclude some people (for example, not everyone has reliable internet access), and you should also consider this in terms of any relevant equalities requirements. It is therefore recommended to allow as many ways of making a complaint or allegation as your institution can effectively manage.

Admissibility of Complaints/Allegations

On receipt of any information that may constitute a complaint or allegation, you will need to establish quickly whether the matter falls within your institution’s jurisdiction. For instance, if the complaint/allegation is about breaches of social media regulation and media monitoring does not fall under your competence but is part of the media regulator’s remit, then the complaint should be forwarded to the competent institution as quickly as possible.

In general, it will be a matter for the competent institution to consider the matter under its own jurisdiction and it will not be necessary for you to analyze the matter further at this stage. However, depending on any agreements in place with other institutions you may choose to conduct further analysis and provide this to the other institution.

If the matter falls within your jurisdiction, you may choose to make a preliminary assessment to decide what is the most appropriate way to deal with it.

What Will You Tell People Who Make Complaints/Allegations?

It is good practice, and in some countries a legal requirement, to both register and acknowledge all complaints and allegations received that meet the formal requirements (Country example - Latvia.pdf). This should be done in a timely matter, either within the time set by law or within a reasonable time established by the oversight body. With emails or online portals, this process can sometimes be automated. You will need to consider how much information to include, but it is helpful to confirm that the complaint/allegation has been received, explain what will happen next (for instance, you might explain the complaint/allegation will be considered in line with policy, and provide a copy of, or link to, the policy) and when the person can expect to hear from you again.

Where you establish that the matter needs to be referred to another institution of competent jurisdiction, it is good practice to tell the complainant this. It is also worthwhile to consider having an agreed procedure in place with other institutions, as appropriate, for referrals. Such agreements can help avoid the frustration of referring matters to an institution that cannot or will not act on your referral. Where the matter is outside the oversight body’s jurisdiction but it is not directly referred or the correct jurisdiction is unclear, it is good practice to suggest possible other relevant institutions to whom the complainant may redirect their concerns. Where the matter does not in fact appear to be within any jurisdiction (for example, the behavior complained about is not in breach of any law but a question of morality) it is good practice to explain this to the complainant, so that the complaint is not then made to other institutions.

Depending on the applicable legislation and your own practice, you may also have to send a copy of the complaint or a summary of the allegations to the party object of the complaint and provide them a deadline to respond. Depending on your country’s system, you may have to blank out personal information related to the identity of the complainant (name, address, employment) according to data protection regulations or because the law foresees the possibility for the complainant/plaintiff to remain anonymous. In any case, this should not prevent you from communicating the nature of the alleged violations contained in the complaint/allegation to the concerned party/candidate. You may have some discretion about when this information is communicated, depending on the applicable legislation.

Consideration should also be given—if the relevant law, policy, or procedure allows it—to whether a complaint will be kept confidential, especially if it is anonymous, and, if so, exactly what will be confidential and for how long. Arguments supporting some level of confidentiality include the adverse impact of publicity surrounding a frivolous anonymous complaint filed right before an election and the interests of law enforcement bodies in being able to not disclose the exact outline of an investigation while it is ongoing. On the other hand, there is an obvious public interest in full disclosure of serious allegations before an election. As the oversight body operating in a politically charged environment, it is important that you develop a policy that addresses how you will handle such issues.

Where you have established that a complaint/allegation is within your jurisdiction, it is good practice (unless prohibited under domestic legislation) to conduct a preliminary assessment. This is a form of triage—to establish whether the matter justifies action and, if so, what the best way of dealing with the matter is (for example, guidance, warnings, or investigation).

It is important that the assessment is in writing, so that you can refer to it later or show how the decision was made. The person conducting the preliminary assessment must also have no conflict of interest so to avoid any suggestion of bias or prejudice. You will also need to consider whether the complainant has any right of appeal against the outcome of the preliminary assessment under your country’s legal system and/or your institution’s established appeals mechanism.

You can choose not to conduct a preliminary assessment and take further action in every matter. In some countries the law actually requires every formally valid complaint be investigated. However, there are significant risks associated with this approach. First, the oversight institution could become overwhelmed with more matters than it has the resources to manage. Second, even if the volume is manageable, dealing with urgent or high-priority matters could be delayed as a result. Finally, this approach can encourage groundless allegations, because the complainant will know that, even if the institution eventually takes no action, the fact it looked into the matter can be used for political advantage. Having a prioritization system that helps sort the complaints and allegations received depending on the nature and severity of the reported breaches/violations can be of some assistance. In some countries, it can be used to winnow out insignificant cases at the outset. In countries that mandate all valid complaints be actioned, it can at least allow the oversight institution to focus first on the more important cases.

There are many ways in which this assessment can be conducted. You will want to consider what is the right method for your oversight institution. Some institutions use a basic form for the assessment, which sets out the questions and or considerations that need to be addressed but leaves the detailed analysis to the person conducting the assessment—you will find an example of a reporting template here (Preliminary assessment form.pdf). Alternatively, a more detailed analysis can be prescribed.

There are many different factors that can be taken into account in deciding whether a matter merits further action and if so how to deal with it. There may be unique factors in any country, but below are commonly used ones:

- Has the institution already assessed, investigated, and/or taken enforcement action on the issue or a similar issue?

- It is always good practice to check whether the matter has been addressed before. In some cases, it is also useful to check with other institutions.

- Would the complaint/allegation, if proved, constitute a violation of the law?

- Sometimes complaints/allegations are based on concerns that may have political or moral importance but are not actually against any rules.

- Is there sufficient evidence to justify an investigation?

- You will need to think about what is a suitable level of evidence to require. Requiring no evidence will encourage groundless allegations, while requiring significant evidence will risk genuine concerns being rejected.

- Is the alleged violation time-barred under relevant law or institutional policy?

- Many countries have a statute of limitations, meaning that after a defined period of time possible violations cannot be actioned. Whether there is such a statute or not, it may be that you will want to have a policy with similar effect. It may not be the best use of your resources to be considering possible violations that took place many years ago.

- Is it appropriate to take the matter further?

- This is the most complex, and often most significant, consideration. In some countries this can involve what is known as a “public interest test,” a term widely used to determine whether further action is warranted.

- If so, what is the most appropriate action?

It is important to consider all possible methods for dealing with a complaint/allegation as part of the preliminary assessment. It is easy to focus only on investigations and enforcement and you may have no discretion, but other approaches can be equally or more effective, if it is open to you to consider them. In some situations it may be more appropriate to deal with a matter by providing guidance or issuing a warning, but this will always depend on all of the facts and circumstances.

For example, where a new political party delivers a donation report in which some figures are slightly wrong, it might be an option to provide some guidance and propose corrective action rather than opening an investigation. On the other hand, where a political party appears to have deliberately tried to hide an illegal donation of substantial value, an investigation is much more likely to be appropriate.

Where a complaint/allegation is rejected for any of the above reasons, it is good practice to explain to the complainant/denouncer the decision taken and the reason for it, and to indicate any right of appeal against the decision they may have.

When Is It Appropriate To Take Further Action?

Whether it is appropriate to take further action can involve a number of considerations, and every case will need to be considered on its own facts, but some common factors that might be relevant are:

- The seriousness of the possible violationâfor example, whether it was deliberate or whether the impact was significant (in terms of sums of money involved, election outcome, public confidence, or some other reason)

- The compliance history of the organizationâis this the first time there has been a potential violation?

- How the violation occurredâwas it due to the responsible officer being absent (ill or even having died) so something was not done, or a less experienced officer stepped in but made a mistake?

The time that has passed since the potential breachâit can be difficult to investigate a breach that took place long ago as documentary evidence may no longer exist and the memories of witnesses may have faded, and there is a risk that it would be unfair to the person accused.

The cooperation of the subject of the complaint or allegationâwhen notified of this issue did the subject immediately apologize and seek to put things right?

You may also want to use indicators (like the ones shown in the template below) to determine whether the violations reported are serious enough and sufficiently grounded to trigger further action. These and other criteria can also be used to consider how complex the matter might be, the priority to be given to it, and in some cases whether it requires particular urgency. See templates for a preliminary assessment form (Preliminary assessment form.pdf) and for a substantive analysis form for complaints and allegations (Substantive analysis form.pdf).

| Indicators | Index | Additional Information or Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Severity of the violation | ||

| Number (once, repeated, multiple cases). |

||

| People involved (number, identity, capacity) |

||

| Financial impact (low, medium, high) |

||

| Source(s) of information | ||

| Reliability of the source of information | ||

| Accuracy of information provided |

The severity of the alleged violation/irregularity is established by using sub-indicators, where a rating of 1 is the least severe and of 3 the most severe:

- Number/frequency of the violation/irregularity.

- Number and identity of involved persons.

- Financial impact (if measurable).

The reliability and accuracy of the sources of the information received are established by using sub-indicators where a rating of 1 is the least reliable/accurate and of 3 the most reliable/accurate:

- Reliability of the source of informationâanonymous/signed complaint, supporting documents (photos, screenshots, interviews), substantiated information.

- Accuracy of information providedâoriginal supporting documentation, precise locations of observed violations accompanied by signed testimonies (with names and phone numbers/email addresses of witnesses), dated photos, screenshots, etc.

The preliminary assessment may also include:

- Seeking further information or clarification from the complainant.

- Making initial and limited inquiries of the subject (although great care should be taken not to take any action that could lead to legal challenge).

- Considering information freely available in the public domain; for example, from press articles and relevant websites.

Audits

An audit is an examination of the contribution and expenditure documentation, banking statements, and other financial records of a submitting entity to assess compliance with existing auditing standards. Therefore, an audit is a type of review conducted in line with auditing and accounting standards and according to the legal framework, which is not necessarily linked to political finance or political finance-centered. In the context of political finance, the aim of an audit is to ensure that financial information included in reports submitted by political parties and electoral contestants is accurate, verifiable, and prepared in compliance with accepted accounting standards.

The audit of financial reports is distinct from the review of financial reports in that the latter usually consists of a thorough control of the substance of the financial reports, while often the legislation does not give the power to audit institutions to review the entirety of the submitted financial reports. A good example in that regard is provided by Montenegro, where two separate institutions are responsible for the review and the audit of political entities’ financial reports. While the Agency for the Prevention of Corruption (APC) is tasked with the review of submitted financial reports and their compliance with the Law on Financing of Political Entities and Election Campaigns, the State Audit Institution (SAI) has authority to perform audits of the reports of political entities benefiting from public funds in accordance with the laws on accounting and audit. The SAI’s remit is narrower than the APC’s.

One of the purposes served by audits is to provide the public with information about the contributions and expenditures of political parties and electoral contestants, as well as the oversight body’s assessment of the accuracy and completeness of reporting entities’ financial reports. In some countries, formal audits form a critical accountability and enforcement mechanism for ensuring the integrity of political finance.

According to the IFES TIDE Political Finance Oversight Handbook, “Auditing of political finance accounts can be done by a professional, independent auditor selected by the political parties and candidates; the enforcement body; or directly by a government agency, such as another enforcement body, tax authority or auditing agency.” In countries where such a mechanism is foreseen, audits are carried out in three different ways.

In some instances, the oversight institution might undertake the audit, especially if it is also an audit institution. When conducting audits, it is good practice that the political finance oversight body develop guidelines/procedures spelling out the process and criteria to either audit or review financial reports. Depending on the oversight body’s resources, it might not be possible for it to comprehensively audit all the reports. Then, it may decide to audit a sample of reports. The selection could be random or based on risk assessment criteria (for example, previous instances/history of noncompliance, complaints/media reports on irregular financing patterns, namely link between donors and participation in public procurement tenders and patterns in the awarding of tenders to main donors) or objective criteria (for example, campaign finance reports of elected candidates, reports of parties or candidates receiving public subsidies). As an illustration, you can find information about the audit work of the U.S. Federal Election Commission, as well as its directive on processing audit reports.

The audit procedures should also determine what will be audited (that is, all or just a sample of the documents, transactions, accounting and financial procedures and other records of the audited entity) and when the reports will be audited (that is, throughout the campaign, after the end of the campaign, every year for political party annual reports, or on a rotative basis.

If the legal framework applicable in your country foresees the certification of financial reports by auditors/chartered accountants, you will have an additional channel to flag potential issues of noncompliance. It is recommended to have in place cooperation mechanisms between the oversight institution and the independent auditors as regards the type of information auditors can access and the type of system they can use (paper-based or online system), as well as the division of tasks and responsibilities. Depending on the applicable legal framework, potential shortcomings could hinder the scope of the audit as auditors may, for example, be legally prohibited from looking at more than specified documents or accessing institutional databases/information, such as the civil registry, to check the permissibility of donors or the tax registry to check the donor records against tax statement records.