Trust and Remuneration: Introduction

Trust is an essential building block of democracy. Constituents in democratic systems expect that the people, procedures, and institutions that comprise the political machine will represent and work on behalf of the people, not to further their own self-interests. That trust – a personal assessment made about the integrity of an individual, situation, process, or entity – is often influenced by numerous experiences, facts, or perceptions.1 Trust in elected officials is thus driven simultaneously, although not always equally, by a person’s experiences with and perceptions of specific politicians, political processes, and political institutions.2

In a democracy, trust in government officials, institutions, or processes is easily taken for granted. However, in the current era of democratic backsliding, there is increased recognition of its incredible fragility. Political and economic crises become cautionary tales in how untrustworthiness engendered by elected officials – due to perceptions about their incomes, whether formal or informal; widescale mismanagement and under-delivery of public services; and corruption – can lead to sustained social unrest, as witnessed in Sri Lanka in 2022. To help build democracies’ resilience to future shocks, IFES set out to gain a more comprehensive understanding of how remuneration impacts democratic trust. The aim of this study is to analyze the remuneration constraints and practices of elected officials in various national contexts.

This report first offers an overview of the dire state of trust in political elites globally and the known links between trust and perceived or real corruption. It justifies the focus on remuneration as a lens into this connection. After outlining the research plan and the unique challenges in conducting research on remuneration for elected representatives, the paper presents the first comprehensive menu of 16 categories of benefits afforded to, and restrictions placed on, elected officials. This multi-method research, conducted in Ecuador, Nepal, New Zealand, and Sri Lanka, uncovered two mutually reinforcing challenges to rebuilding trust in elected officials through remuneration: constituents’ perceptions that officials receive more financial compensation than they actually do, and officials’ receipt of numerous informal benefits in practice. This comparative analysis generated five recommendations for remuneration reform presented in the final section of the report. If those recommendations are followed, they stand to motivate a virtuous cycle of remuneration practices and trust in officials.

Motivation: Understanding Global Trends In Democracy, Trust, Corruption, And Equality

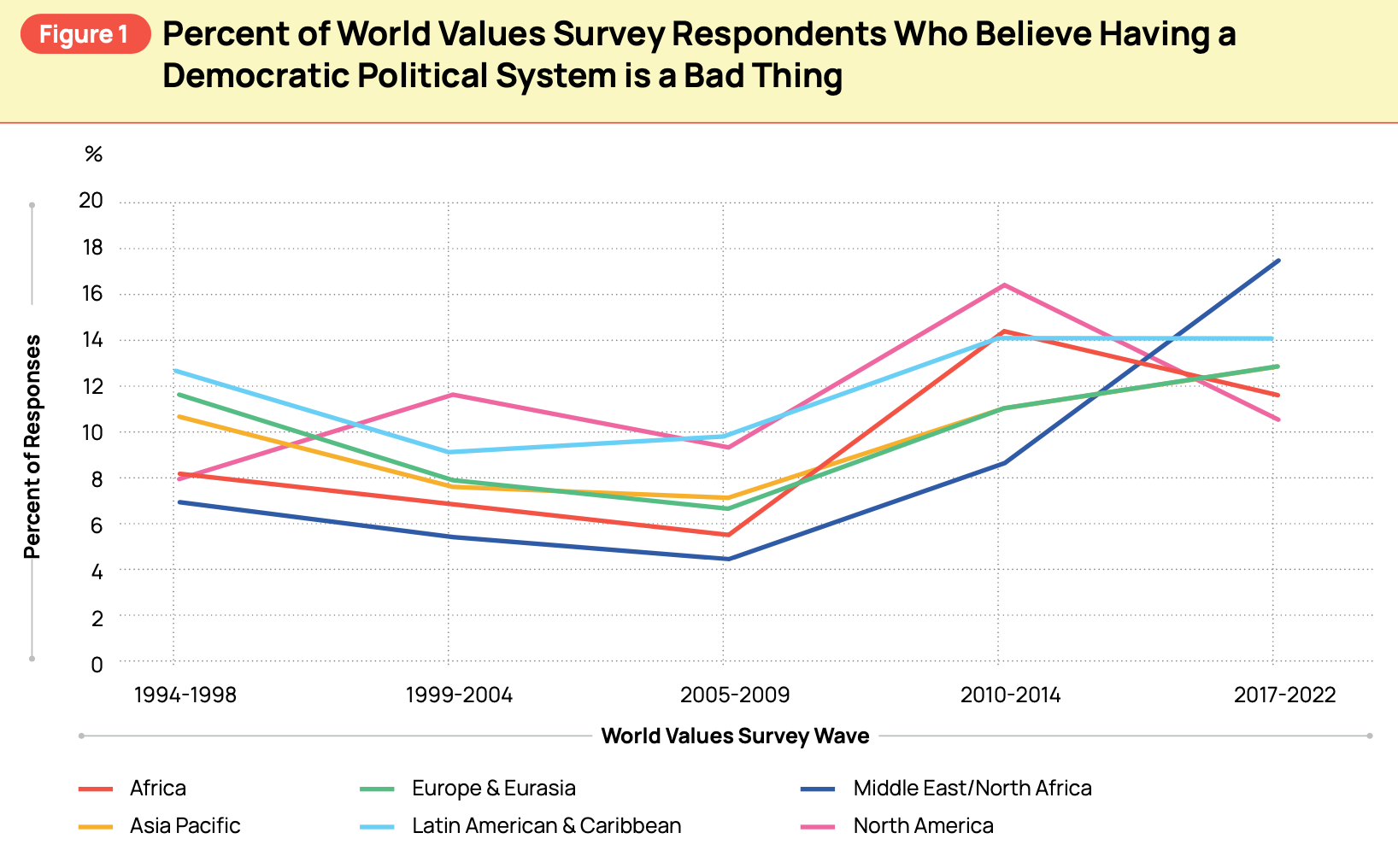

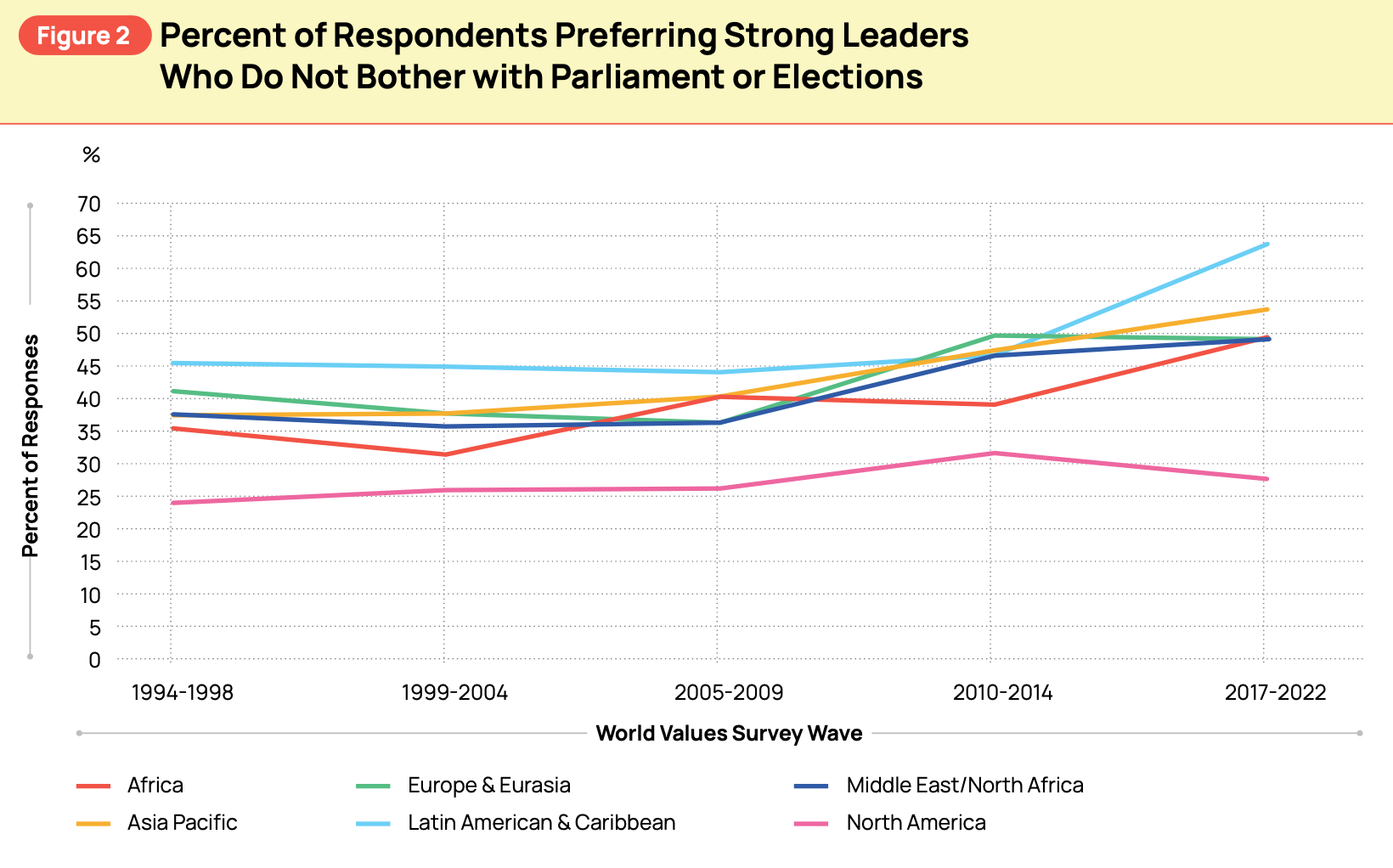

Fewer people today than 20 years ago believe in the normative and functional promises of democracy. Since the mid-2000s, people in every region of the world increasingly say it is bad to have a democratic political system, with that number nearly tripling in some regions according to data from five waves of the World Values Survey.3 At the same time, there is a growing preference in every region for leaders “who do not have to bother with parliament and elections”.4 Objective measures of democracy also indicate a global decline in its quality in the same time period.5

This current era of global democratic backsliding is characterized – and was arguably driven in part – by declining trust in democratic institutions, processes, and political leaders. These worrying trends demand investigation into the root causes of this distrust.

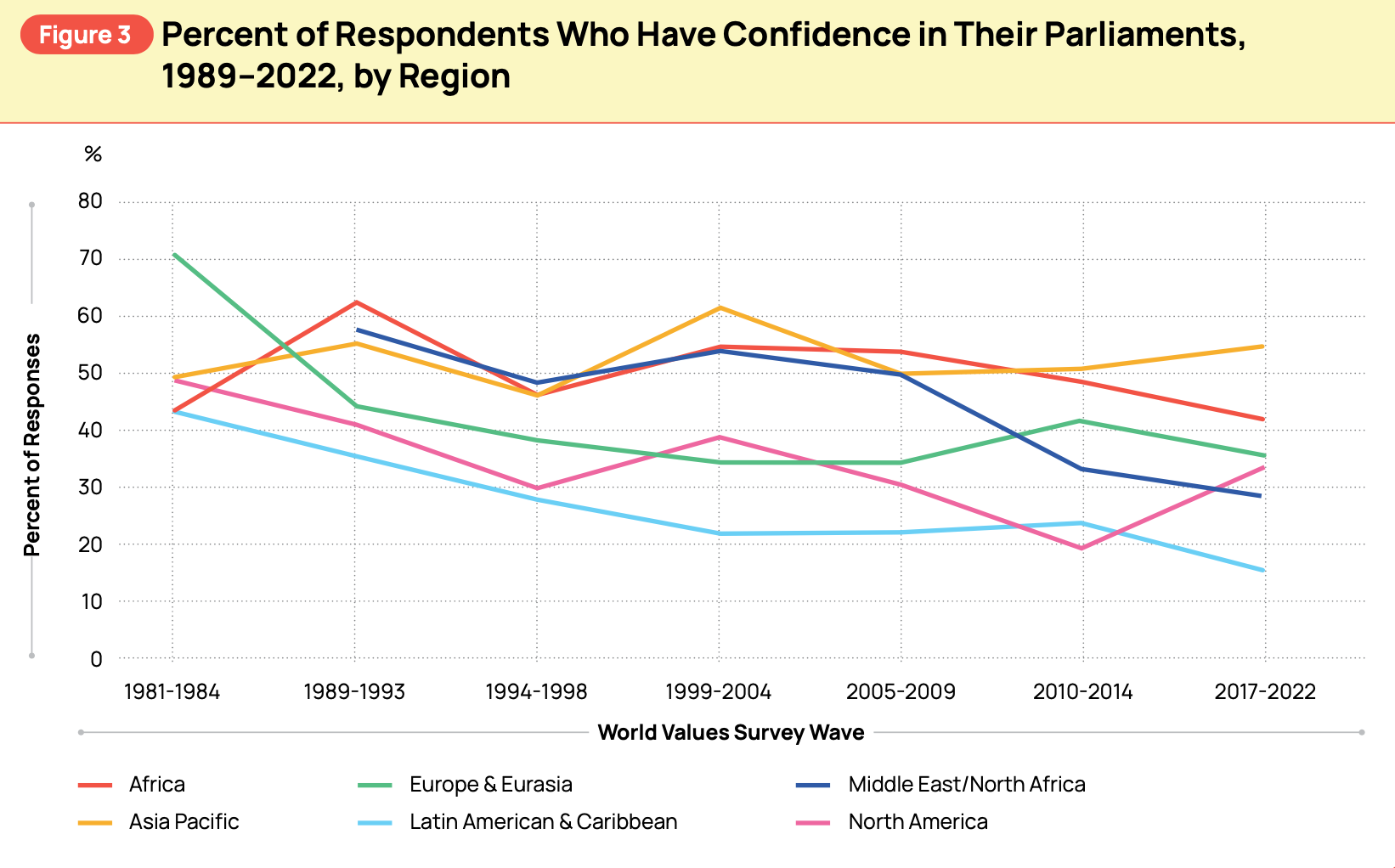

Overall dissatisfaction with and, in some places, abandonment of democracy is driven in part by declining trust in elected institutions. Confidence in parliaments, along with courts or justice systems, has been on the decline across most regions since the early 2000s.6 The Edelman Trust Barometer conducted in November 2023 found that respondents in more than half of the 28 countries surveyed distrust their governments.7 Citizens also perceived their state and local authorities to be corrupt at alarmingly high rates.8

These gaps in institutional trust can extend to the people who serve in prominent government or civil society roles, particularly when those individuals are ensnared in corruption scandals. Corruption has become normalized in many countries – both in everyday life and at the highest political levels. According to the most recent wave of the World Values Survey, civil servants – including members of the police and the judiciary – are perceived to be at least somewhat corrupt in most regions. Alarmingly, as many as 60 percent of respondents from Africa and Latin America think all or most of the civil servants in their countries are corrupt.9 Other surveys reinforce those findings. An IPSOS poll on trustworthiness conducted in 28 countries in 2021 found that politicians generally and government ministers specifically were considered the two least trustworthy types of people.10

Distrust – at both the individual and institutional levels – is intrinsically tied to and can be worsened by corruption. Corruption can be defined as an “untrustworthy behavior,” a betrayal of “entrusted power,” or a “breach” of interactional or “formal justice.”11 Both corruption at the individual or institutional level and distrust of individuals or the system can be exacerbated by social inequality. Unfortunately, inequality is at an all-time high and rising in many parts of the world.12 Trust, inequality, and corruption can mutually reinforce each other when corruption is low and equality and trust are high as part of “virtuous” cycles; alternatively, societies plagued by high inequality, sustained distrust, and continual corruption fall into “vicious” cycles.13

When investigating this causal relationship among the levels of inequality in a society, perceived and actual corruption, and generalized trust, measurement and conceptualization issues abound. For example, low levels of trust have been found to be “both a cause and consequence of corruption.”14 The best-known methodologies capture perceived corruption, such as Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index. However, perceptions of corruption are only part of the puzzle. The more difficult task is identifying all possible inroads and methods of corruption to form an “objective” measure of actual corruption. To address this measurement challenge, researchers and practitioners can disaggregate corruption into measurable, observable practices.

One way corruption manifests is through the formal benefits (e.g., diplomatic passports) and informal kickbacks (e.g., gifts) that elected officials receive by virtue of their offices. There is some disjointed scholarly research on remuneration practices in individual countries, usually focusing on elites’ reasons for preferring different remuneration structures15 or the effects of remuneration policy changes in those countries.16 However, a systematic international review of remuneration best practices and challenges is lacking. Given the connection between corruption and trust, a better understanding of current remuneration practices for elected officials and people’s impressions of those practices can help make inroads to strengthen democratic trust.

Real-world circumstances further motivate this research and suggest a strong link between compensation for elected officials and levels of political trust. Namely, the Government of Sri Lanka defaulted on its debts for the first time in history in April 2022, leading to the president and cabinet resigning, a complete collapse of the economy, unprecedentedly high inflation, fuel shortages, lack of healthcare, and other socio-economic and political issues. The default precipitated the Aragalaya (“The Struggle” in Sinhala) protest movement, which also brought to light difficult conversations about political corruption. Although the economy is, at the time of this writing, showing signs of stabilization due to robust international assistance and a bailout package from the International Monetary Fund, economic disparities between the political elite and ordinary Sri Lankans have become a cornerstone of debates about Sri Lanka’s democratic future. The Aragalaya movement acutely evinced the need to rebuild confidence in the democratic system – particularly in elected officials.

Scope and Approach

With the Aragalaya movement serving as the catalyst for this study, IFES researchers examined remuneration structures and norms for elected officials in four countries: Ecuador, Nepal, New Zealand, and Sri Lanka. The countries were chosen according to a most-similar and most-different in- and out-of-region design that permits robust conclusions that are not narrowly context-dependent. The driving factors in case selection were democracy score,17 development level,18 executive and legislative types,19 population,20 GDP per capita,21 and region. The researchers selected two comparative cases within the region, along with one out-of-region example (Ecuador) that was most similar on all other counts. The two within-region cases were selected to be most different (New Zealand) and most similar (Nepal) along four other dimensions: democracy score, development level, population, and GDP per capita.22

The research took place in three distinct stages. First, researchers conducted a thorough review of each country’s legal code, looking for all explicit legal provisions about remuneration for elected officials. Principally, the research focused on members of the legislative branch – meaning the parliaments in Nepal, New Zealand, and Sri Lanka and the National Assembly in Ecuador. Throughout this document, all elected officials are referred to as Members of Parliament (MPs) or Assembly Members, as appropriate to each country’s context. The scope of this study focuses on the remuneration rules relevant to all MPs and Assembly Members, not those in leadership positions. However, additional benefits provided according to rank are discussed when relevant.

During the legal analysis stage, it became clear how diffuse these rules and regulations can be. Remuneration standards are often dispersed throughout legal codes, necessitating review of various laws, regulations, policies, and practices across ministries and within multiple segments of the code. Some of those segments are not readily available for public scrutiny (e.g., not available at ministries or public institutions). The researchers also understood that even where rules and regulations are clearly outlined de jure, officeholders typically benefit from some degree of informal benefits that the law does not outline. The challenge then became how to identify the full set of possible remunerations.

Recognizing that remunerations are not always explicitly provided for or prohibited in the law, the researchers undertook a series of structured interviews with current and former MPs and Assembly Members in each country to gain insights on the additional benefits that elected officials know and utilize. During this second stage of research, the researchers also interviewed people who did not hold elected positions – namely journalists, academics, and members of civil society – to identify other benefits and better understand how much the public knows about their elected officials’ remuneration. The non-MP interviewees thus needed to be positioned to be aware of the intricacies of MP compensation. In total, the researchers conducted 31 interviews between September 2022 and September 202323 with roughly the same number of elected officials and others who did not hold elected positions in each country. The scripts for the interviews appear in Annex 2. Originally envisaged as 30-minute conversations, the interviews tended to run closer to one hour. They were conducted in a mix of English and the respondents’ native languages, with the assistance of trusted interpreters. The authors then hand-coded the interview data to identify practices within and patterns across the four countries’ remuneration practices.

Compensation is a particularly sensitive and opaque topic, especially among elected officials. The research was designed to capture detailed insights from current and former MPs about compensation, checked against non-MPs’ knowledge of the same. The non-MPs were able to provide some anecdotal (but non-representative) insights into public perceptions of elected officials. However, the goal of this research was to understand how those practices influence – or at least co-vary – with public perceptions. Since the leading regional surveys do not include all the countries in this study, the researchers conducted a survey of the Sri Lankan public in Stage 3 (hereinafter, the “Sri Lanka Survey”). The Sri Lanka Survey included 151 Sri Lankans from various ethnic, linguistic, and geographic backgrounds who responded to questions about what drives their trust or distrust of elected officials. It was conducted online in English, Tamil, and Sinhala between July and November 2023.

Research Challenges

Remuneration is a conceptually complex issue, and researching such a ubiquitous topic came with unique challenges.

Verification was the greatest challenge for this research. At times, no paper trail existed to triangulate information that the researchers gathered through interviews about a certain practice in a country. In such cases, the researchers triangulated among interviewees of different backgrounds. At other times, data available to the public from official sources was out of date and updates could not be reliably attributed. For instance, the Sri Lankan government’s official immigration website outlining diplomatic passport rules24 links to a list of “proposed” persons to be issued diplomatic passports, although the document itself does not bear a state insignia or a date.25 There was also no list of specific eligible persons to cross-reference. In many cases, the combination of research methods enabled the researchers to overcome this type of limitation. Where relevant, the following analysis identifies these transparency limitations.

The specter of unauthorized benefits (e.g., bribes, informal payments, corruption) loomed over this research, especially during interviews with MPs. To respect cultural sensitivities, the researchers did not ask any direct questions about bribes or corruption.26 However, in several interviews, MPs offered insights into the state of such unauthorized benefits in their countries.

Together, these challenges extended the research period beyond what was originally envisaged. Nevertheless, the combination of the three methods of data collection and generation enables us to draw generalizable conclusions about the composition of remuneration packages and to identify common opportunities and challenges to remuneration as a mechanism for building trust between elected officials and the electorate.

References

1 On defining trust, see Uslaner, E. M. (ed.) (2018). The Oxford Handbook of Social and Political Trust. Oxford University Press. In particular, see chapters “Trust and Democracy” by Warren, M., and “Measuring Trust” by Bauer, P. C., & Freitag, M.

2 Emmons, C., Vickery, C., & Shein, E. (2022). Democracy and the Crisis of Trust. Foreign Policy, November.

3 Inglehart, R., Haerpfer, C., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., Lagos, M., Norris, P., Ponarin, E., & Puranen, B. (eds.). (2022). World Values Survey: All Rounds - Country-Pooled Datafile. www.worldvaluessurvey.org. Madrid, Spain and Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute and WVSA Secretariat. Dataset Version 3.0.0.

4 Ibid.

5 Gorokhovskaia, Y., & Grothe, C. (2024). Freedom in the World 2024: The Mounting Damage of Flawed Elections and Armed Conflict. Freedom House; Lindberg, S. (ed). (2024). Democracy Report 2024: Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot. Varieties of Democracy Institute, Gothenburg, Sweden.

6 Inglehart, et al., supra note 3.

7 Edelman Trust Institute. (2024). 2024 Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report.

8 Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., Lagos, M., Norris, P., Ponarin, E. & Puranen, B. (eds.). (2022). World Values Survey Wave 7 (2017–2022) Cross-National Data-Set. Version: 4.0.0. World Values Survey Association.

9 Ibid.

10 IPSOS. (2021). Global Trustworthiness Index 2021.

11 You, J. (2017). Trust and Corruption. In Uslaner, E. M. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Social and Political Trust pp. 473–496. Oxford University Press.

12 Qureshi, Z. (2023, May 16). Rising Inequality: A Major Issue of Our Time. Brookings.

13 See Ulsaner, E. M. (2008). Corruption, Inequality, and the Rule of Law: The Bulging Pocket Makes the Easy Life. Cambridge University Press; Rothstein, B. & Uslaner, E. M. (2005). All for All: Equality, Corruption, and Social Trust. World Politics, 58(1), 41–72.

14 Morris, S. D., & Klesner, J. L. (2010). Corruption and Trust: Theoretical Considerations and Evidence from Mexico. Comparative Political Studies, 43(10), 1258–1285.

15 See, e.g., Holm Pedersen, L. H., Pedersen, R. T., & Bhatti, Y. (2018). When Less is More: On Politicians’ Attitudes to Remuneration. Public Administration, 96(4), 668–689.

16 See, for instance, Braendle, T. (2014). Does Remuneration Affect the Discipline and the selection of Politicians? Evidence from Pay harmonization in the European Parliament. Public Choice, 162(1/2), 1–24.

17 Evaluation of both Freedom House status and average Variety of Democracy (V-Dem) scores calculated in 2022. The V-Dem average was calculated across the annual Liberal Democracy, Polyarchy, and Participatory Democracy index scores. Twenty-year regional trends also consulted.

18 Based on World Bank income groups.

19 Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143(1/2), 67–101. Updated by authors with Economist Intelligence Unit political structure profiles.

20 World Bank Open Data.

21 World Bank Open Data. GDP per capita.

22 For more on case selection, see Annex I.

23 Interviews in Ecuador were completed prior to the dissolution of the National Assembly in May 2023.